In Argentina, a bid to make language gender neutral gains traction

Karina Galperin, directora de la Maestría en Periodismo UTDT/La Nación, analizó las ventajas del uso del lenguaje de género inclusivo.

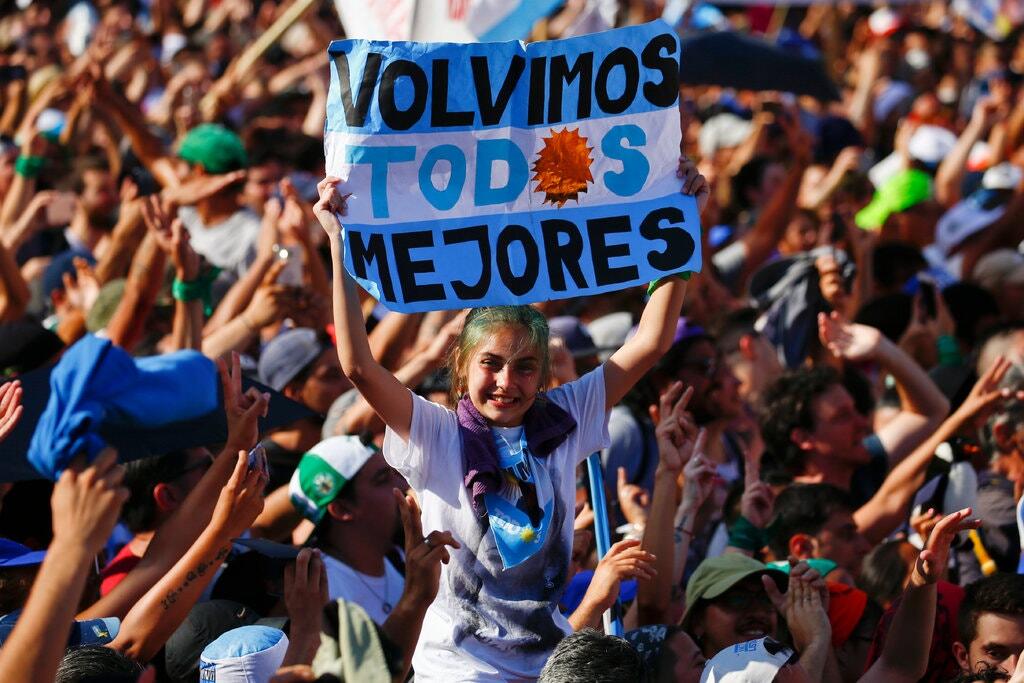

Supporters of President Alberto Fernández replaced the “o” in todos — “everyone” — with a sun so the word would no longer be masculine.Credit: Marcos Brindicci/Associated Press.

BUENOS AIRES — Three days into Argentina’s coronavirus lockdown, the country’s president called on men and women, Argentinos and Argentinas, to cooperate with the effort.

He also appealed to “Argentines,” using a gender-neutral term that doesn’t exist in traditional Spanish grammar.

It was not the first time President Alberto Fernández, who took office in December, publicly used gender-neutral language.

But his decision to do so again at a moment of public crisis underscored the reach of a movement challenging the longstanding rules of language and working to make the Spanish used in Argentina more inclusive.

“We’re always talking about equality — and the truth is that language reveals the inequalities that exist in society at large,” said a Buenos Aires city judge, Elena Liberatori.

Last year, Judge Liberatori set off a controversy by issuing a ruling in which ordinarily gendered words were spelled with an “e” instead of the “a” or “o” that generally denote the feminine or the masculine in Spanish.

The quest to make Spanish less gendered is not limited to Argentina.

In the United States, for instance, some politicians and scholars, and even the Merriam-Webster dictionary, have embraced the word “Latinx." It is an alternative to Latino, the masculine form of the word used to encompass everyone as the default in Spanish.

Not everyone welcomes the change though.

The push for gender neutrality has also been met with staunch opposition around the world, including among the foremost experts on the Spanish language. The Royal Spanish Academy, which oversees the most authoritative dictionary in the language, regards the new formulations as an aberration.

What makes Argentina notable is how widely embraced the new forms have been not just among activists but also in academic and government spheres.

In recent years, gender-neutral formulations have become increasingly common in university publications, government documents and even a few judicial rulings, even as they continue to be a subject of fierce debate among the public at large.

Mr. Fernández has been the most prominent user of gender-neutral language in a country where many have welcomed the change.Credit: Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

Judge Liberatori said she had long been conscious of the way language can uphold societal norms. When she was sworn in as a judge in 2000, the sign outside her door read “juez,” rather than the female term for a female judge: “jueza.” She changed it.

Later, when she issued a ruling using gender-neutral language, Judge Liberatori faced a complaint filed by a group of lawyers before the city’s Council of Magistrates, which has the power to punish judges for breaching norms.

The council sided with Judge Liberatori, ruling that judges could write their rulings with the “e” and saying it would publish a manual for the use of gender-neutral language.

“We’ve joked that we should name the manual after” the lawyer who filed the complaint, said Cristina Montserrat Hendrickse, an attorney who represented Judge Liberatori in the matter.

Ms. Hendrickse, who is transgender, believes that adopting gender-inclusive language can have a profound effect on societal and cultural norms. “It recognizes that there aren’t just men or women,” she said.

Yet, she acknowledged that she herself doesn’t use it in day-to-day communication.

“I’m more than 50 years old,” she said. “It’s too difficult for me to change my whole way of speaking.

Her 22-year-old daughter, Erika Sofía Hendrickse, though, “uses it constantly,” Ms. Hendrickse said.

That kind of widespread acceptance makes Ariel Muzzupappa, a 22-year-old artist who is nonbinary and also uses words with the “e” variation, feel “more comfortable.”

“It makes me feel more included,” the artist said, “like I’m no longer the weird one.”

There is no consensus among experts on how long people have been using the letter “e” to neutralize gendered words in Spanish, said Karina Galperín, a literature professor at the Torcuato Di Tella University in Buenos Aires.

“It is the result of a very, very broad historical process,” she said, even if its newly widespread use may make it appear like a recent phenomenon.

Judge Elena Liberatori issued a ruling last year in which she used gender-neutral terms. Credit: Victor R. Caivano/Associated Press

Before the use of the “e” found broad adherence, Spanish speakers who wanted to be more inclusive used both genders, or the @ symbol or an “x.” The “e” has been more widely embraced because it’s easier to pronounce.

“It has clear advantages, but some people find it totally repulsive,” Ms. Galperín said. Even though there “is a lot of unanimity in rejecting the use of the masculine form as the default, the solution to that problem is not so unanimous,” she said.

The Royal Spanish Academy argues that gender-neutral proponents are trying to solve a problem that doesn’t exist.

Spanish, the academy says, already has a way of taking into account both genders. Under the rules of its grammar, they note, the masculine form of words can be used in the plural to encompass everybody. So “Argentinos” with an “o,” for example, can be used to refer to citizens of Argentina of any gender.

But by expressly rejecting the old rules, gender-neutral proponents are making a larger point, said Santiago Kalinowski, the director of the Department of Linguistic and Philological Research at the Argentine Academy of Letters. (His views do not represent those of the institution.)

“This recourse explicitly places itself outside of the linguistic rules so that it’s more striking,” he said. “This intervention is interesting because its objective is not grammatical, but rather political and social, to create a consensus to change the culture and eventually change laws.”

The shift in language coincided with the rise of a feminist movement in Argentina that coalesced around a campaign against femicide, or the killing of girls and women because of their gender. That campaign, called “Ni Una Menos,” (“Not One Less”), was critical to broadening political support for legalizing abortion, a legislative priority for Mr. Fernández.

Soon after he came into office, some government departments began adopting genderless language. The pension system, for instance, released a guide for all its staff in inclusive language. But it stopped short of ordering its use in official documents.

Mónica Roqué, the agency’s general secretary for human rights and gender, helped draft the manual and credits youth movements for pushing the language changes.

“They prompted us to think about this,” she said. “That transgression of using a letter that is neither ‘a’ nor ‘o’ really made us think about what it means.”

The National Institute Against Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racism in Argentina has also started using inclusive language in some official resolutions. But it has refrained from using the “e” formulation out of fear that it would create more befuddlement than awareness.

“In general, there is a desire to always use inclusive language,” said Victoria Donda, the head of the institute. “But inclusive language can’t leave some people out.”

In poorer neighborhoods, Ms. Donda said, people are not as used to hearing the letter “e” replace the “a” or the “o,” and that can lead to confusion.

Still, Ms. Donda’s 5-year-old daughter always speaks with the “e.”

“I have to use it with her, because she corrects me if I don’t,” she said.

Link: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/15/world/americas/argentina-gender-language.html