Escuela de Gobierno

En los medios

22/10/19

¿Estará la Argentina segura en las manos del Peronismo?

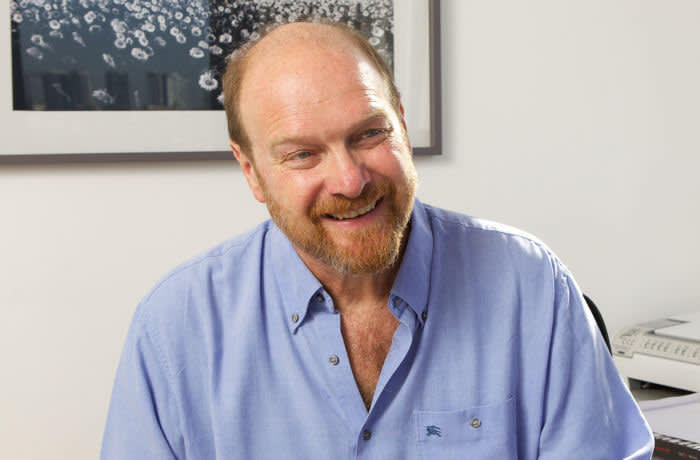

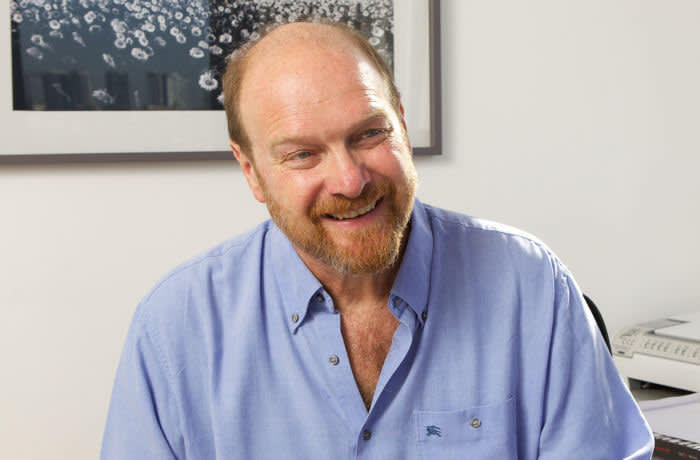

Eduardo Levy Yeyati, decano de la Escuela de Gobierno UTDT y director académico del Centro para la Evaluación de Políticas basadas en Evidencia (CEPE), fue consultado por Financial Times acerca de sus expectativas económicas en un posible gobierno de Alberto Fernández.

The victor of this Sunday’s election in Argentina will inherit one of the world’s most unenviable economic messes.

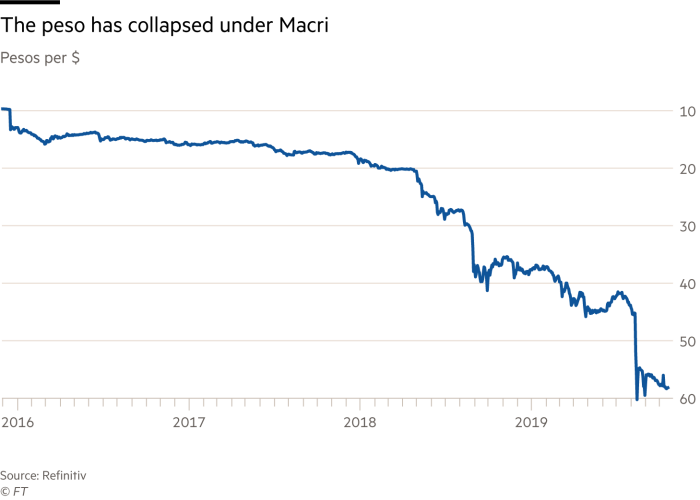

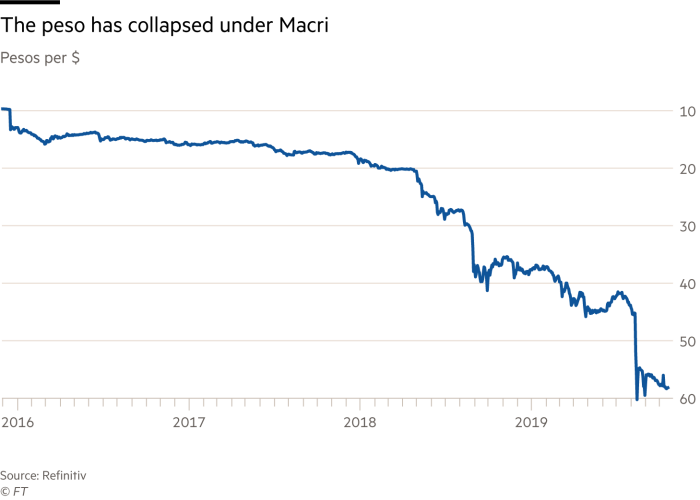

Inflation is running at 55 per cent a year, the economy is in a deep recession, poverty is rising, billions of dollars have fled the country, the peso has plunged and Argentina is unable to pay its $100bn foreign debt. It sounds an all too familiar story in a country that aspired to European levels of prosperity in the early 20th century but has consistently disappointed ever since.

This time was supposed to be different: Mauricio Macri, scion of one of the country’s wealthiest families, came to power four years ago promising that his market-friendly policies and business savvy would finally put the Argentine economy right.

But after a series of blunders that led to another IMF bailout last year, Mr Macri has achieved what few thought possible, according to a senior executive at an international bank in Buenos Aires: he will hand over Argentina’s economy in a worse state than it was when he inherited it in 2015 from Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, a leftwinger criticised by international investors for her repeated bouts of state intervention.

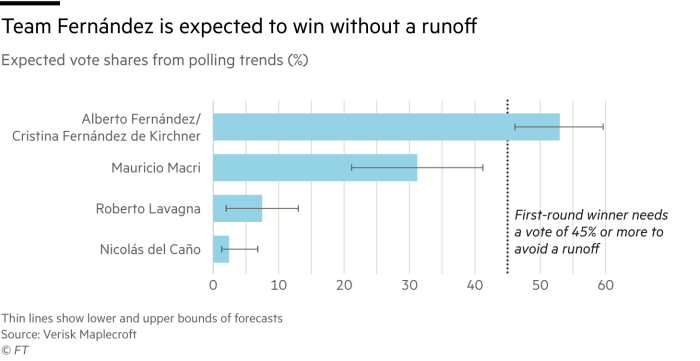

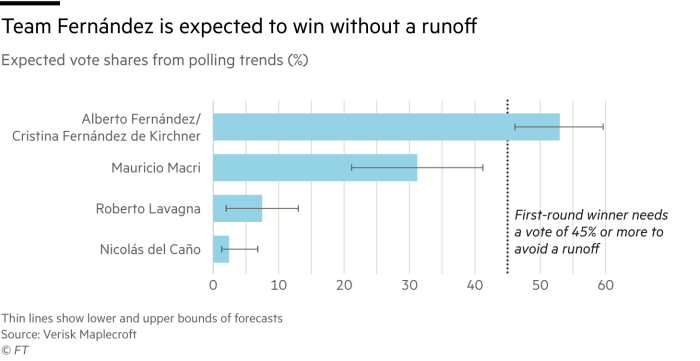

Somewhat improbably against the dire economic backdrop, Mr Macri is running for a second term. But few even in his own team expect him to win. A national primary on August 11, widely regarded as a good barometer of sentiment, was won handsomely by the main opposition candidate, the centre-left Peronist Alberto Fernández, whose running mate is Ms Fernández de Kirchner.

Mauricio Macri, Argentina's president, and presidential candidate Alberto Fernández, who is expected to succeed him © Reuters

Mauricio Macri, Argentina's president, and presidential candidate Alberto Fernández, who is expected to succeed him © Reuters

Mr Macri has since attempted to relaunch his faltering campaign under the slogan “#Sí se puede” (‘Yes we can’). But recent opinion polls — not always to be trusted — suggest that Mr Fernández’s lead may have widened. A final batch published before the election by the newspaper Clarín predicts that the Peronists will win by a crushing margin of between 16 and 22 percentage points, more than enough to avoid a runoff.

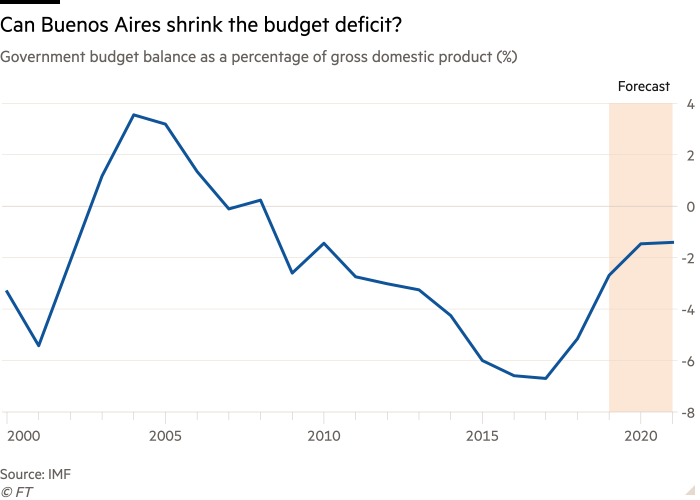

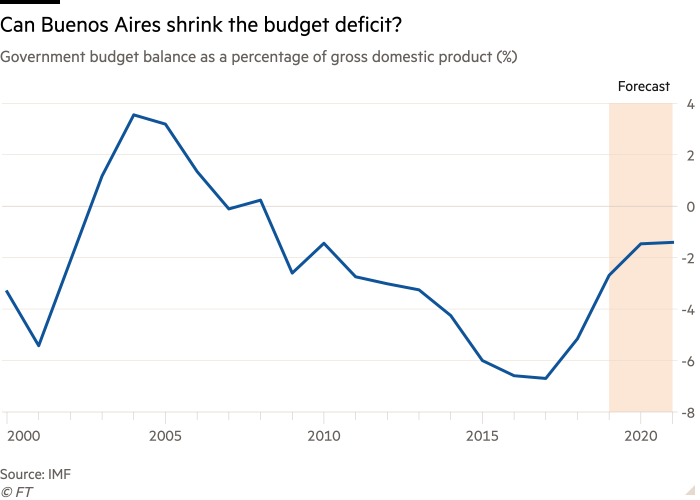

Mr Macri has found himself under attack from both sides: liberals criticise him for not acting faster at the start of his term to cut Argentina’s bloated budget and for relying excessively on interest rates to bring down inflation in a country addicted to regular price rises. Leftwingers attack him as a man who governed for the rich.

“The Argentine economy is rather like a sick man bleeding heavily in the street,” says Luis Tonelli, chair of the department of political science at Buenos Aires university. “There is no time to analyse his condition. You need to call an ambulance and start pumping blood into him before he collapses completely.”

Market confidence collapsed after the August primary election result, principally because of investor fears that a Peronist return to power would mean a repeat of the interventionist, big-state policies first favoured by the populist general Juan Perón in the 1950s.

Heavy falls in the peso and the stock market forced Mr Macri to reimpose the exchange controls he had scrapped amid much fanfare at the start of his administration. But $12bn had already fled the country since the primary and economists say Argentina remains vulnerable to a market meltdown unless the election victor acts quickly.

“The agenda is the same whoever wins,” says one chief executive of a major Argentine company. “Exchange controls will have to stay in place, debt needs to be rescheduled and the market remains closed for now to Argentina and its companies . . . then there is high public spending, the budget deficit and runaway inflation: any economic programme has to lower inflation.”

The most urgent need is to renegotiate Argentina’s debt, which shot up under Mr Macri’s administration, largely as a result of the record $57bn IMF bailout programme which he sought amid a currency crisis last year.

“There is very little that a new government can do without a deal with the IMF and the rescheduling of [bondholder] debt,” says Eduardo Levy Yeyati, dean of the school of government at Torcuato Di Tella university in Buenos Aires. “Without this double deal, it is very hard for Argentina to grow.”

The problem, Mr Levy says, is that Argentina needs a debt deal quickly to avoid running out of money, and private sector creditors are unlikely to agree to one unless they are offered generous terms. The fund, however, is smarting from the travails of its biggest-ever loan and is likely to press for bondholders to take sizeable losses to ensure that it is not accused of lending public money to rescue private investors.

“It’s a Catch-22 with the timing,” says Mr Levy.

The IMF has not made further disbursements on its loan to Argentina since August’s market crash. Its new head Kristalina Georgieva said last week that the fund remained “fully committed to work with Argentina” and was “very interested to see what policy framework would be put in place”.

But with Mr Fernández the likely election victor, the fund is preparing for uncomfortable talks. The Peronist candidate has been sharply critical of the IMF during his campaign, alleging that it should share responsibility for the country’s plight with Mr Macri, and accusing it of facilitating capital flight with its record-breaking loan. “But nothing [Mr Fernández] has said so far indicates that it will not be possible to work out an agreement,” says an international financier close to the discussions.

Kristalina Georgieva, the new managing director of the IMF © EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

Kristalina Georgieva, the new managing director of the IMF © EPA-EFE/Shutterstock

A wider concern among the business community in Buenos Aires is over the policies Mr Fernández may follow to revive the sickly economy.

As cabinet chief under the 2003-07 Peronist presidency of Néstor Kirchner, Mr Fernández was known as a pragmatic moderate. He continued in the post when Mr Kirchner’s wife Cristina Fernández de Kirchner became president, only to resign in July 2008 over her decision to impose heavy export taxes on the country’s farmers.

Mr Fernández has since largely stayed out of the limelight, juggling his time between working as a political consultant, a lawyer and a university lecturer, until Ms Fernández announced in May that she would run as vice-president on a ticket with him (the two are not related). The move was widely seen as a masterstroke, allowing Ms Fernández a partial return to power despite high voter rejection rates after presiding over a period of poor economic management and rampant public corruption.

So far, the strategy has worked. Mr Fernández has campaigned across the country while his vice-presidential candidate has been largely absent, often abroad in Cuba visiting a sick daughter.

Political analysts say this dynamic could change after the pair win power. “Alberto Fernández is a transparent Trojan horse,” says Mr Tonelli, the political scientist. “You can see straight through him: in his belly is Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.”

Pedro Sánchez, a trucker in the northern city of Resistencia is, like many voters, backing Mr Fernández through gritted teeth.

“I have my doubts about Alberto. After all, he is from the Kirchners’ inner circle,” says Mr Sánchez, who voted for Mr Macri in 2015 because he was tired of the corruption and authoritarianism associated with the Kirchners. He feels “cheated” over the dire economic situation but is not optimistic that the new president will do any better. “Governing Argentina must be very difficult. It is very unpredictable and Argentines are terribly complicated people — but that is just how we are.”

Mr Tonelli says one of Mr Fernández’s first challenges after a win would be to define his relationship with his running mate. “They hated each other [when he resigned] and they still hate each other,” he says. “But she has most of the political structure of Kirchnerism and most of the votes, and Alberto has nothing . . . It will be very difficult for him. He is caught between the rock of the IMF and the hard place of Kirchnerism.”

Opinions differ on how active Ms Fernández might be as vice-president but there is general agreement that she will want to extricate herself from nine separate corruption investigations dating back to her time in power.

Gustavo Grobocopatel, Argentina’s 'soy king' who runs the Grupo Los Grobo agribusiness, wants a calm handover of power to the new president © Javier Pierini

Gustavo Grobocopatel, Argentina’s 'soy king' who runs the Grupo Los Grobo agribusiness, wants a calm handover of power to the new president © Javier Pierini

“Her number one priority is to get herself and her family out of legal trouble,” says Walter Stoeppelwerth, chief investment officer at Portfolio Personal Inversiones in Buenos Aires. “And Alberto Fernández’s number one priority is to make her problems go away. He is many things but he isn’t dumb. He is very smart, although he is not surrounded by the smartest people.” As well as the potential tension with his former boss, analysts fear Mr Fernández will struggle to hold together a disparate coalition that ranges from orthodox economists to radical social activists with little in common apart from an interest in seeing the end of Mr Macri’s government. “This coalition will not be a long-lasting one,” says Jimena Blanco, head of Americas research at Verisk Maplecroft, a risk consultancy. “It will eventually fracture because of conflicting policy and ideological views within it — the question is not if but when.” Many are concerned about how much sway La Cámpora — a militant youth movement founded by Ms Fernández’s son, Máximo Kirchner — could hold in a Peronist administration. Argentina’s powerful union movement has also long been a thorn in the side of governments, leveraging industrial action into higher wages.

Maximo Kirchner, the son of Cristina Fernández de Kirchner and founder of the youth movement La Cámpora © AFP/Getty Images

The new president will also have to deal with groups such as the Workers’ Confederation of the Popular Economy (CTEP). Fiercely independent and capable of mobilising large numbers of discontented jobless workers, CTEP strikes fear in the heart of Argentina’s middle classes, recently leading noisy protests in upmarket shopping malls.

“There is a question mark over how Alberto’s political personality will develop once he becomes a leader. No one knows,” says Juan Grabois, a pugnacious 36-year-old lawyer and outspoken leader of CTEP, which is aligned with Ms Fernandez’s Peronist coalition. “I hope he will try to relieve the pain of the most poor and contain the voracity of some economic groups that want fast and easy profits.”

Mr Grabois recently proposed radical land reform that included expropriating 50,000 plots of land and banning any Argentine from owning more than 5,000 hectares. Mr Fernández distanced himself from the proposals.

Mr Fernández has almost entirely avoided interviews or news conferences with international media during his campaign and has only sketched vague outlines of his economic policy, which centres on renegotiating debt, a national pact to control inflation and reviving growth by boosting domestic consumption. Perhaps his most important decision, assuming he wins, will be the choice of finance minister. The appointee will lead the complex debt renegotiations with the IMF and private bondholders, as well as having the task of reviving the floundering economy.

The two names most often mentioned from his inner circle are his economic advisers Matias Kulfas and Cecilia Todesca, who held senior roles at the central bank during Ms Fernández’s presidency but are considered inexperienced. Martin Redrado, Guillermo Nielsen and Emmanuel Alvarez Agis, all senior economic officials during the Kirchner years, are seen as more “market-friendly” candidates.

Workers' activist Juan Grabois, whose CTEP movement is aligned to the Peronist coalition © Getty

Another decision will be how open Argentina remains to the rest of the world for trade and investment. “Being open to the world doesn’t mean being stupid,” says one source close to Mr Fernández. “Macri surrendered to the world naked. We want a relationship with the world that benefits Argentina.”

Gustavo Grobocopatel, chief executive of the Grupo Los Grobo agribusiness, says one of the most important aims after the election is to achieve a calm handover. “Every time the government changes, there is a crisis and everything starts again from zero.”

Argentina, adds Mr Tonelli, is “not so much a stop-go economy as a crash-go economy”.

There is little optimism about the capacity of a new government to tackle deeply rooted economic problems. “The state of Argentina’s economy is no more than a symptom of our culture,” says Eduardo Costantini, a billionaire real estate developer and art collector. “It is not a [question of] technical error.”

At the heart of Argentina’s problem is its refusal to live within its means, he argues, pointing out that the peso has lost 98 per cent of its value against the dollar in successive devaluations since 1991.

“We don’t accept here the trade-offs needed to reduce inflation,” he says, joking drily that in Argentina austerity is a “forbidden word”.